Lost in the Wilderness

Photographs (c) Kalpesh Lathigra

Lost in the Wilderness

Photographs (c) Kalpesh Lathigra

Lost in the Wilderness

Photographs (c) Kalpesh Lathigra

Lost in the Wilderness

Photographs (c) Kalpesh Lathigra

Lost in the Wilderness

Photographs (c) Kalpesh Lathigra

Lost in the Wilderness

Book Launch: Webber Space Gallery, London, March 17

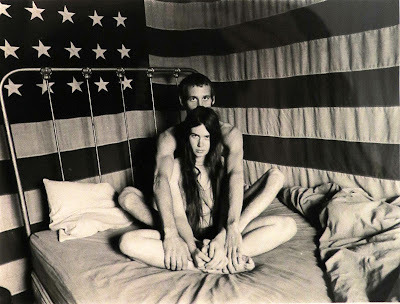

Lost in the Wilderness / Kalpesh Lathigra

It’s funny how, as children, we don’t question the games we play or the slow burn of what we take in through films and books and the simple conversations we have. It’s hard to think of a child of my generation not playing cowboys and Indian or watching John Wayne and Gary Cooper in action against the Indians, who always were the enemy.

In these games I was always the Indian, never the cowboy. Why? Because, as a child, India – the subcontinent – is where I was seen as coming from, even though I was born and raised in Forest Gate, London and still live there today.

This fact alone made it my destiny never to be the hero. Later I would read "The Autobiography of Malcolm X" by Alex Haley, "Soul on Ice" by Eldridge Cleaver, "Notes of a Native Son" by James Baldwin; books that were not part of the school curriculum but rather the curriculum of friends who felt abandoned by the school. Those texts transformed many of us marginalized kids growing up in the 1970s and ’80s; they were the words and experiences I could genuinely identify with.

In 2006 I was in New York and a family friend Mark Hewko gave me a copy of "Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee," Dee Brown’s history of the American West, told from the point of view of Native Americans. I read it with an urgency that led me to Ian Frazier’s "On the Rez," about the Oglala Sioux who live on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. I became determined to visit some of these places. I found a charity, Lakota Aid, run by Brenda Aplin in Devon, England. Brenda had spent time on Pine Ridge and seen first hand the challenges faced by the community on Pine Ridge. The charity was raising funds for propane gas (for heating) and better housing during the harsh winters. They put me in touch with Garvard Good Plume, Jr, an elder at Pine Ridge, who would become my guiding light.

I made my first trip in the summer of 2007. At first I photographed very little; I wanted to meet the community there, to see and feel the land. I was concerned about voyeurism and stereotypes and whether I would be able to connect with the people. But those fears were soon laid to rest by the ease with which people accepted me. They told me stories about life on the reservation – how it used to be, what their lives were made up of now, and about their hopes and fears for the future. They treated me with kindness, guidance and dark humor. More often that not I was called “the real Indian”.

There are serious problems on Pine Ridge: there is poverty, unemployment, alcoholism, violence and a high rate of suicide among the young men and women. But it is important to consider the belief that lies behind their determination to preserve their traditions, to keep the Lakota language alive despite the challenges faced. I wanted to make a series of photographs that would not add to the cliches about Native Americans, but would be more lyrical and metaphorical, using ideas around historical landscapes, still life and portraiture. These photographs are of people, places, moments, and things I connected with. They say something about my own experiences as the child of immigrants seen through the experiences of others that I can relate to.

“Lost in the Wilderness”

Exhibition and Book Launch

Webber Space Gallery, London on March 17

I asked Kal about the beautiful production of his book: "My brother Jay Lathigra, who is NYC based, did the design and he has made it sing. The printer in Istanbul has done a wonderful job in their care and attention, plus John Wesley Mannion, a master printer at

Light Work in Syracuse, made the match prints. All are part of the team who made the book what it is."